The night after my last day at EMC I wrote a blog article that remains unpublished. Maybe some day I will share it. But today I feel it is a little too personal to release to the public. Its theme centered on a life on autopilot. Living taking each step following the momentum of the previous one. I realized that night that part of my life for many years was on autopilot. Then I thought of the flash crash of 2010.

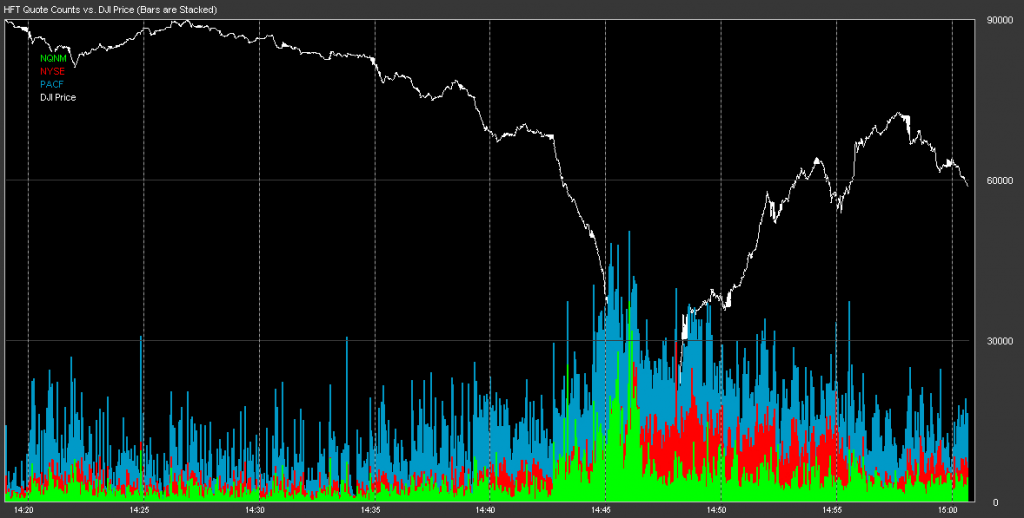

On 6 May 2010 the US stock market plunged 9% (over 1000 points) and recovered those losses within minutes. $1.3 trillion in market value vanished and then reappeared in less time than it takes to use the restroom. The stock market was in a death spiral driven by a emotionless autopilot.

On 6 May 2010 the US stock market plunged 9% (over 1000 points) and recovered those losses within minutes. $1.3 trillion in market value vanished and then reappeared in less time than it takes to use the restroom. The stock market was in a death spiral driven by a emotionless autopilot.

A New York Times article written a few months after the crash dissected the events. The crash started on the afternoon of 6 May when a single trade, a mutual fund selling $4.1 billion in futures, drove some prices down significantly. The article continues:

Normally, a sale of this size would take place over as many as five hours, but the large sale was executed in 20 minutes. … [The mutual fund’s automated selling] algorithm was programmed to execute the trade “without regard to price or time,” which meant that it continued to sell even as prices dropped sharply…As [other trading algorithms bought heavily then] detected that they had amassed excessive “long” positions, they began to sell aggressively, which caused the mutual fund’s algorithm in turn to accelerate its selling.

The rout continued for minutes–an eternity for computers that execute trades in fractions of a millisecond–until an automatic stabilizer cut in and paused trading for five seconds. Then markets recovered. Five seconds. That’s what ultimately saved the US stock market. Forcing the market to do nothing for five seconds.

Software running on high speed computers shows us in time lapse what happens when decisions are made quickly and without regard to the long term. These algorithms use short-term information to feedback into an algorithm making instantaneous decisions. These programs greedily search for an optimum only milliseconds in the future. They fail to see a true optimum that may be weeks, months, or years ahead.

This brings me to my reflective moment on departing erstwhile employer. I knew in high school I would study computers in college. I knew in college I would go to graduate school. I knew then I would work in the silicon valley for a high tech firm. My career wrote itself. And I never questioned it until two months ago.

I still may very well go back to the high tech industry I love. But I am so lucky to have a year off to break the cycle of automation. Software may need five seconds. People may need months. If you find yourself wondering if you are following a path with you feet moving without thought. Maybe you need a five second pause.

I heard about the flash crash in a TED talk a few years ago. I didn’t know it was stopped by a trading pause. I like the idea of a “life pause” to stop our own automatic decision making!